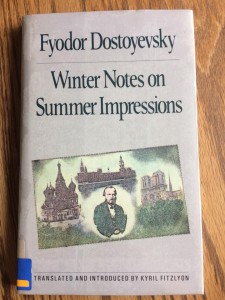

I stumbled upon this book in a charity shop in England while looking for second-hand DVDs of film classics. I hadn’t known about its existence previously, but I was intrigued by the blurb. Actually, no, whatever the blurb had said, I was going to be purchasing it; it was a Dostoevsky book I didn’t already own. It was first published under the title Summer Impressions by John Calder in 1955, but this edition was revised by Kyril FitzLyon and published by Quartet Books Limited in 1985.

|

|

In the summer of 1862, Dostoevsky travelled to Western Europe, discovering France and paying his one and only visit to Britain. On his return, he published these impressions of his trip. It is thought that Dostoevsky intended to reveal and explain the nature of the French and English people to his fellow Russians, but something much more important happened. For, in these notes, Dostoevsky appears to have introduced the ideas and themes that were to preoccupy him in many of his masterpieces: the effect of European civilisation on the Russian character, the influence of individualism on the West, the hollowness of 19th Century material progress and political achievements, the inevitability of the proletarian revolution.

Dostoevsky spent one week in London, and three in Paris; his experiences in these cities brought life to ideas which can be clearly identified in The Devils, Crime and Punishment and The Brothers Karamazov. It is puzzling why Dostoevsky endured three weeks in Paris, as he reports that Paris bored him to death! London, on the other hand, overwhelmed his senses. He concluded that the outstanding trait of the French is hypocrisy, and the English, pride. Dostoevsky travelled through Germany, and he is scathing about the Germans. He declares that Berlin is incredibly like St Petersburg. He recognises that his opinions are probably unfair: ‘Blow me, I thought to myself, it was really hardly worth while spending a back-breaking forty-eight hours in a railway carriage only to see the replica of what I had just left.’ He accused the Berliners of looking ‘German’ and said ‘no sight was more horrible’ than a Dresden woman. He was also irritated by the new bridge at Cologne as he felt the town was ‘too proud of it.’ He believed that he was only charged a toll to cross the bridge because the collector ‘guessed that he was Russian.’

In these notes, Dostoevsky chats to the reader as though he were a good friend, touchingly revealing his personality. In Chapter 1, he admits that he is “unable to give you the most accurate information. I must willy-nilly be untruthful occasionally. You tell me, in short, that all you want are my own impressions, provided they are sincere.”

Chapter 2 begins the telling of the comical story of Dostoevsky’s train journey into Paris, but he opens the chapter with. “’Frenchmen are not rational and would consider themselves most unfortunate if they were,’” a phrase written by Denis Fonvizin. Dostoevsky reacts: “All such phrases, which put foreigners in their place, contain, even if we come across them now, something irresistibly pleasant for us Russians. We keep this secret, sometimes, even from ourselves. For there are in this, certain overtones of revenge for an evil past.” He describes his companions in the train carriage in mocking terms; of a quiet Englishman, he writes: “He reads all day without lifting his head a book of that very small English print which only English people can tolerate and even praise for its convenience, and at precisely ten o’clock at night he took off his boots and put on slippers.”

Chapter 3 is entitled, ‘Chapter 3 Which is Quite Superfluous’, and it certainly steers the reader away from the subject of the book, exploring Dostoevsky’s opinions on Fonvizin, rural village councils, ‘The Brigadier’, the Chevalier de Rohan, cotton-wool padding in European ladies’ dresses, Russian literature, peasants and the character of Chatsky, to name but a few. At the close of this long chapter he begins to ask for forgiveness for digressing, then writes, “But anyway, there is not need to insist on being forgiven. This chapter of mine is superfluous, as you will remember.” And it is.

Chapter 4 resumes the story of Dostoevsky’s train journey towards Paris. He finds himself in pleasant conversation, on and off, with a Swiss gentleman who sits opposite him. Dostoevsky is mystified when, on the entry of four new passengers, a group of baggage-less Frenchmen, the Swiss man falls silent and cannot be coaxed into further talk. The new passengers completely ignored Dostoevsky and the Swiss gentleman, giving Dostoevsky the opportunity to study them:

“They all wore a thin sort of frock-coat, terribly shabby and threadbare, little better than those worn by our officers’ batmen or by servants in the house of a not very well-off country squire. Their shirts were dirty, their neck-ties very bright and also very dirty; one of them wore the remnants of a silk kerchief, of the kind which are constantly worn and become stiff with grease after fifteen years’ contact with the wearer’s neck. The man also had studs with imitation diamonds the size of a hazel nut. However, there was a certain smartness and even dash about them. All four appeared to be of the same age – thirty-five or thereabout – and though their faces were dissimilar, they themselves were very much alike. Their faces, somewhat haggard in appearance, had the usual little French beards which also looked very much alike. They sat and smoked with a somewhat nonchalant air and affected complete indifference.”

The four men left the train at the next station, and the Swiss man immediately snapped shut his book and began talking to Dostoevsky again, explaining that the men were the police, whose sole intention was to study these foreign travellers. He explains that they would already have had their names, and copies of their documents, but needed to make detailed descriptions of these foreigners. Dostoevsky discovered, once he arrived in Paris, that each hotel took down his particulars in great detail, and he knew that all of this information was immediately sent to the authorities:

“’But what do you want it for?’ I asked.

‘Oh, it is es-sential,’ replied the landlady, with a polite drawl on the word ‘essential’. But at the same time entering my height in the book. ‘Now, monsieur, your hair? Fair… er… very fair, really… straight…’

She made a note of the hair as well.

‘Would you mind, monsieur,’ she went on as she put down her pen, left her seat and came up to me with all the politeness she could muster, ‘over here, a step or two nearer the window. I must have a look at the colour of your eyes. Hm… light colour…’

And again, she glanced questioningly at her husband. ‘A bit greyish,’ remarked the husband with a particularly business-like, even worried expression. ‘Voila,’ he said and gave his wife a wink, pointing at something over one of his eyebrows, but I understood perfectly well what it was he was pointing at. I have a small scar on my forehead and he wanted his wife to take note of this distinguishing mark, too.”

Chapter 5 embarks on Dostoevsky’s general observations about London and Paris. He notices something that the modern traveller might recognise even today about Paris: “Paris tries to contract, willingly, lovingly somehow tries to make itself smaller than it really is, tries to shrink within itself, smiling benignly as it does so.” And yet, of London, he says: “The impression [London] left on my mind was of something on a grand scale, of vivid planning, original and not forced into a common mould. Everything there is so vast and so harsh in its originality.” But, he writes, “Both Paris and London have one thing in common: the same desperate yearning, born of despair, to retain the status quo, to tear out by the roots all desires and hopes they might harbour within them, to damn the future in which perhaps even the very leaders of progress lack faith, and to bow down in worship of Baal.”

Dostoevsky finds London to be something “out of the Apocalypse”: “The immense town, forever bustling by night and by day, as vast as an ocean, the screech and howl of machinery, the railways built above the houses (and soon to be built under them), the daring of enterprise, the apparent disorder which in actual fact is the highest form of bourgeois order, the polluted Thames, the coal-saturated air, the magnificent squares and parks, the town’s terrifying districts such as Whitechapel with its half-naked, savage and hungry population, the City with its millions and its world-wide trade, the Crystal Palace, the World Exhibition…” Not much has changed since then! Dostoevsky is amazed at how the streets of London fill up with men and women at the beginning of the weekend, seeking “salvation in gin and debauchery.” He remarks on the area of Haymarket where “prostitutes swarm by night in their thousands. You will find old women there and beautiful women at the sight of whom you stop in amazement. There are no women in the world as beautiful as the English.” Well, I’m not sure about that!

Chapters 6 and 7 offer a richly colourful and cruel excavation of the ‘bourgeois’. He has them uttering, “I don’t exist, I don’t exist at all; I am hiding, walk past, please, don’t take any notice of me, pretend you don’t see me: pass along, pass along!” Of the French, he opines, “All Frenchmen have an extraordinarily noble appearance. The meanest little Frenchman who would sell you his own father for sixpence and add something into the bargain without so much as being asked for it, has at the same time, indeed at the very moment of selling you his father, such an impressive bearing that you feel perplexed. Go into a shop to buy something, and its least important salesman will crush you, simply crush you, with his astounding nobility.” Dostoevsky’s judgement on France continues with: “Though socialism is possible, it is possible anywhere but in France,” because of the bourgeoisie. Cuttingly, Dostoevsky states that “The Frenchman loves attracting the attention of authority in order to suck up to it, and he does it in a completely disinterested sort of way, with no thought of an immediate reward; he does it on credit, on account.” As a Brit living in France, I have to admit that this seems to be the case even today.

Chapter 8 presents a farcical romp in the telling of the story of the bourgeois Bribri and Ma Biche. Their scandalous story runs to its end, and that is the end of the book! No further comment from Dostoevsky is provided! I absolutely love this short book; it reveals so much about the man, Fyodor Dostoevsky, and I now feel as though I’ve spent time with him exchanging our very personal views on the people of Europe.

***

Want to know about VM Productions’ Dostoyevsky-Los Angeles Project and about the films we make? Want to participate in our projects? Sign up to get tickets to the premiere of our movie (currently in post production), Dostoyevsky Reimagined-BTS and

grab our FREE e-books !

|

|

Follow us on Twitter, Facebook, Google+, Pinterest, Tumblr, Instagram, Goodreads.

Leave a Reply