Independe

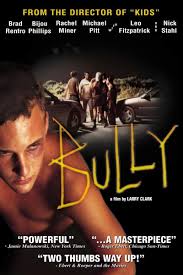

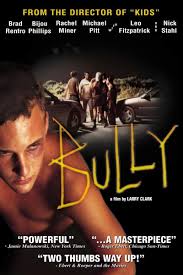

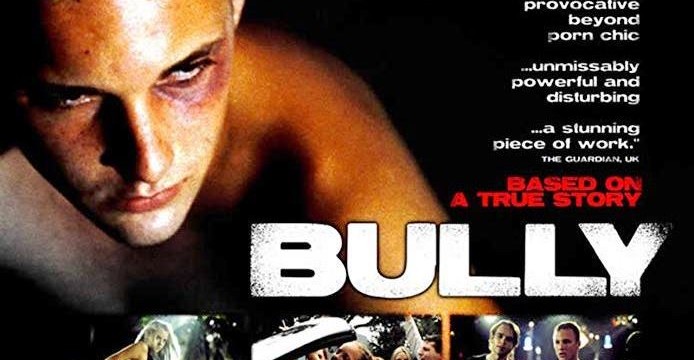

nt director Larry Clark’s psychological crime drama film

Bully–a depiction of the 1993 murder of Bobby Kent by his own circle of friends–was released in 2001 to sharply polarized criticism, the negative reviews targeting its allegedly gratuitous–and painfully straightforward–portrayal of teen-on-teen violence. One of the few positive reviews came from Roger Ebert, who a

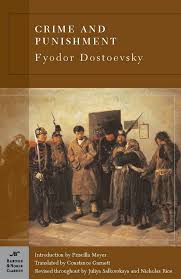

rgued that the film succeeds because it “made a leap into the teenage mindscape” and it “has all the mess and cruelty and thoughtless stupidity of murder.” If that statement is true, then Dostoyevsky’s own leap into the young adult mindscape in

Crime and Punishment has all the mess and cruelty and thoughtful

intelligence of murder. Raskolnikov is a lot smarter and more conscientious in his deed than the wayward, floating adolescents of

Bully are. But the psychological hoops they jump through, the reasons and justifications they contrive and their own heroic self-image matched up against their mounting fear of the punishment creeping nearer, are the same. By axe, by knife or by gun; the mechanism of murder remains remarkably consistent.

First As Farce…

What mental gymnastics are involved in turning the most anti-human of deeds into a simple, maybe bothersome, errand? Raskolnikov and Bobby Kent’s killers know–it requires a refusal to think that this person is a flesh-and-blood person with a mother and beating heart and fuzzy childhood memories in favor of an abstract notion of justice. The thing

must be done, because justice demands it and the good of the social whole depends on it. Raskolnikov’s justifications for the murder of Alyona Ivanovna–the immoral, unlikeable pawnbroker begin with an “embryo of an idea” (66) that because this woman who leeches off everyone in her path, she deserves–nay,

requires-eradication. He even publishes an essay on this, titled “On Crime,” arguing that “there are certain persons who…have the perfect right to commit breaches of morality and crimes, and the law is not for them” (246). Call it vigilante justice–to Raskolnikov, it’s justice nonetheless. The kids of

Bully may be a lot less eloquent in their justification, but it’s the same justification. Bobby is a parasite on their social harmony and well-being in t

he parking lots and strip malls of their town of Hollywood, Florida–he is evil, he is predatory, he is cruel, he’s a

bully–and so Bobby must go.

It can’t remain only an abstraction though. The idea needs to germinate and needs to grow from something cold and intellectual and far-fetched into the most seemingly natural and organic thing of all, as boring and as necessary as pulling a tooth. It happens through repetition, through a gradual, escalating process of making the unfamiliar familiar and the unfathomable seem as if it could not be any other way. Here is where Dostoyevsky’s psychological genius comes through, and where I believe Clark also makes his successful leap into the murderous mindscape. Raskolnikov first entertains the idea of murder when he overhears two young men complaining about Alyona Ivanovna in a tavern one night, and jokingly-but-seriously daring to “kill that old woman and make off with her money, without the faintest conscience-prick” (65). Raskolnikov recognizes this as mere “youthful talk and thought” that would never be followed through with, except…maybe…by him. It does begin as an “embryo of an idea” in his mind and he ruminates upon it until “it had an almost completely mechanical effect on him, as though someone took him by the hand and started pulling him with unnatural force, irresistibly, blindly, without his objections…into something preordained.” The possibility evolves into necessity, and then into reality.

If Raskolnikov’s justification evolves in the recesses of his own mind, that of the Bully killers evolve in the collective space of the group. It begins as an “embryo”–Lisa one day suddenly declares “I want him dead.” Of course, it’s not taken seriously, but then it cycles around the group, gathering seriousness and intention and planning and further evidence for Bobby’s need for disposal, until it morphs into the deed itself. Consider the cyclical nature of this conversation below:

Lisa: I want him dead. He treats everyone like that. He’s always mean. He’s always cruel. He beats you up. He’s the source of everyone’s troubles, Marty. And even still, he’s going to finish high school and go to college and probably get rich.

Marty: Yeah, and I’m going to be delivering pizzas to him in Weston. How would we get a gun?

Lisa: My ma has one.

Marty: He’s dissed me! He’s treated me like that my whole life!

Lisa: Let’s kill him. I want him dead.

There’s no one particular moment in this dialogue that pinpoints the transition from a joke to an intention, nor is there in any of the other very similar conversations held between the seven teenagers before the murder. Rather, it’s the gradual accumulation of conversations like these that pave the way, much like Alyona Ivanovna’s murder, into something “preordained.”

What’s Next?

The law finds its way at the end of both works though. Raskolnikov, through a grueling combination of mind games at the hands of investigator Porfiry Petrovich, the encouragement of pious streetwalker Sonya, and his own temptations toward the freedoms of confession, finally does come forward and is sent to Siberian prison. Much like the evolution of the murderous intent in the social setting, the teens of Bully stumble their way to confession and punishment as a group. First, they are terrified of being found out. So they all convince themselves that they were not the individual murderer, they were only an accomplice. Someone else did it, not me, really. Then the desire to seek reassurance from an authority figure that it’s really not that big of a deal comes through. They start asking their parents–hypothetically, if someone were to maybe kill another person, what would the penalty be? For a minor? For an accomplice? What if the victim really deserved it? And then the desire to confess rears its head in the final scene in its backward, collective way, when the teenagers all accidentally confess on the stand in the process of arguing with each other about why the other person was truly at fault. Whether or not they actually wanted the punishment they deserved is up for debate. But they really didn’t do anything to prevent it from coming after them.

Perhaps then, the question is not “how does one talk themselves into their crime?’ but rather, “how does one talk themselves into their punishment?”

Larry Clark’s Bully is currently streaming on Hulu.

——————————————————–

Bully. Directed by Larry Clark, performances by Brad Renfro, Bijou Phillips, Rachel Miner, Michael Pitt, Daniel Franzese, Kelli Garner, and Nick Stahl, Lions Gate Films, 2001.

Dostoevsky, Fyodor. Crime and Punishment. Translated by Constance Garnett, 1914. Translation revised by Juliya Salkovskaya and Nicholas Rice .

Ebert, Roger. Rev. of Bully, by Larry Clark. The Chicago Sun-times. 20, July 2001.

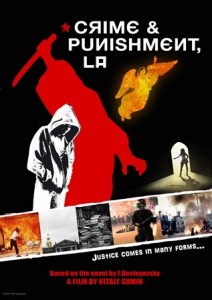

Crime and Punishment, LA, the third film of VM Productions Dostoyevsky-LA Project (following Shades of Day & Notes From the New World) – a re-envisioning of Dostoyevsky’s classic novel transported to LA during the riots of 1992 is in active development. The script has made it to the top 8 for the European Co-Production Matchmaking Program, which was featured during the panel of SXSW

*****

Want to know about VM Productions‘ Dostoyevsky-Los Angeles Project and about the films we make? Want to participate in our projects? Sign up to get tickets to the premiere of our movie (currently in post production), Dostoyevsky Reimagined-BTS and grab our FREE e-books !

Follow us through our social media on

Twitter, Facebook, Pinterest, Tumblr, Instagram, Goodreads.

The visual material – fair use by Kate Panney

nt director Larry Clark’s psychological crime drama film Bully–a depiction of the 1993 murder of Bobby Kent by his own circle of friends–was released in 2001 to sharply polarized criticism, the negative reviews targeting its allegedly gratuitous–and painfully straightforward–portrayal of teen-on-teen violence. One of the few positive reviews came from Roger Ebert, who a

nt director Larry Clark’s psychological crime drama film Bully–a depiction of the 1993 murder of Bobby Kent by his own circle of friends–was released in 2001 to sharply polarized criticism, the negative reviews targeting its allegedly gratuitous–and painfully straightforward–portrayal of teen-on-teen violence. One of the few positive reviews came from Roger Ebert, who a rgued that the film succeeds because it “made a leap into the teenage mindscape” and it “has all the mess and cruelty and thoughtless stupidity of murder.” If that statement is true, then Dostoyevsky’s own leap into the young adult mindscape in Crime and Punishment has all the mess and cruelty and thoughtful intelligence of murder. Raskolnikov is a lot smarter and more conscientious in his deed than the wayward, floating adolescents of Bully are. But the psychological hoops they jump through, the reasons and justifications they contrive and their own heroic self-image matched up against their mounting fear of the punishment creeping nearer, are the same. By axe, by knife or by gun; the mechanism of murder remains remarkably consistent.

rgued that the film succeeds because it “made a leap into the teenage mindscape” and it “has all the mess and cruelty and thoughtless stupidity of murder.” If that statement is true, then Dostoyevsky’s own leap into the young adult mindscape in Crime and Punishment has all the mess and cruelty and thoughtful intelligence of murder. Raskolnikov is a lot smarter and more conscientious in his deed than the wayward, floating adolescents of Bully are. But the psychological hoops they jump through, the reasons and justifications they contrive and their own heroic self-image matched up against their mounting fear of the punishment creeping nearer, are the same. By axe, by knife or by gun; the mechanism of murder remains remarkably consistent. he parking lots and strip malls of their town of Hollywood, Florida–he is evil, he is predatory, he is cruel, he’s a bully–and so Bobby must go.

he parking lots and strip malls of their town of Hollywood, Florida–he is evil, he is predatory, he is cruel, he’s a bully–and so Bobby must go.

Leave a Reply