To be ‘big in Japan’ is not usually a commendation. The term was originally coined in the 1960s to describe Western music artists who were popular in Japan, but unable to garner interest in their home country. But Fyodor Dostoyevsky really is big in Japan.

The seeds for Dostoyevsky’s appeal to the Japanese reader may have been sown far back in time, when the ruling authorities of Japan during the 17th Century closed off the country to all outside influences, particularly fearing the spread of Christianity. The entry of all foreigners to Japan was banned, and Japanese people were forbidden to leave the country. This isolation from the rest of the world continued, surprisingly until the mid-19th Century, when the shogun passed political power to the emperor. The feudal system ended, and Japan opened its shores to the almost inevitable lure of capitalism. This revolution is known as the Meiji Ishin.

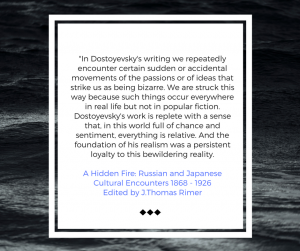

The sudden influx of Western literature heralded a wave of great change. Cultures that were very alien to the Japanese way of life seduced the creative minds of a nation hungry to explore the ‘new world’. Kawabata Kaori, a scholar of Russian literature, suggested that in 1908, the total number of translations from Russian literature exceeded those of English literature. He believed the reason for this was the Russian writers’ strength in describing deep suffering due to rapid civilization, coupled with a search for solutions to these problems; this aroused the sympathy of the Japanese people, as they were facing similar problems.

Father of the Japanese short story, Ryunosuke Akutagawa, believed that the reason that Japanese people were so passionate about modern Russian literature, especially the books of Dostoevsky, was because, of all of the Western civilizations, Russia was least far removed from the Japanese disposition. In Dostoyevsky’s characters, the Japanese reader saw ‘warts and all’ realism combined with deep (and often dark) soul-searching at a time when the Japanese nation was taking a really good self-analytical look at itself in the arena of the world at large. Akutagawa was in no doubt that the writings of Dostoyevsky had a direct impact on the new literature of Japan.

In private letters to his contemporaries, Akutagawa often wrote about his reflections on stories such as Demons, The Brothers Karamazov, and The House of the Dead. On Crime and Punishment he writes, ‘in the novel there is no plastic’ and describes ‘scenes of immense power’. He refers to Dostoyevsky’s writings in several of his own short stories, including Monkey, the plot of which is heavily influenced by The House of the Dead. He mentions The House of the Dead in another of his stories, Daidōji Shinsuke: The Early Years. Akutagawa read Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov in English translation sometime between 1917 and 1918, and his own story of The Spider’s Thread is a re-telling of a very short fable from the novel known as the ‘Parable of the Onion’, where an evil woman who had done no good at all in her life is sent to hell, but her guardian angel points out to God that she had in fact done one good deed in her life: she once gave an onion to a beggar. So God told the angel to take that onion and use it to pull her out of hell. The angel very nearly managed to pull her out, but when other sinners began to hold on to her so they could also be pulled out, she kicked at them, saying that the onion was hers and she was the one getting pulled out, not them. At that moment, the onion broke and the woman fell back into hell, where she remains.

In private letters to his contemporaries, Akutagawa often wrote about his reflections on stories such as Demons, The Brothers Karamazov, and The House of the Dead. On Crime and Punishment he writes, ‘in the novel there is no plastic’ and describes ‘scenes of immense power’. He refers to Dostoyevsky’s writings in several of his own short stories, including Monkey, the plot of which is heavily influenced by The House of the Dead. He mentions The House of the Dead in another of his stories, Daidōji Shinsuke: The Early Years. Akutagawa read Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov in English translation sometime between 1917 and 1918, and his own story of The Spider’s Thread is a re-telling of a very short fable from the novel known as the ‘Parable of the Onion’, where an evil woman who had done no good at all in her life is sent to hell, but her guardian angel points out to God that she had in fact done one good deed in her life: she once gave an onion to a beggar. So God told the angel to take that onion and use it to pull her out of hell. The angel very nearly managed to pull her out, but when other sinners began to hold on to her so they could also be pulled out, she kicked at them, saying that the onion was hers and she was the one getting pulled out, not them. At that moment, the onion broke and the woman fell back into hell, where she remains.

One of Akutagawa’s final writings before he committed suicide at the age of 35 after struggles with his mental health, was Spinning Gears, a monologue from a man in a psychiatric hospital who is convinced that he is ‘one of those responsible for the crimes committed in hell’. After struggling with light and darkness, shifting between heaven and hell, the protagonist’s reading of Crime and Punishment does little to help his return to sound mental health.

Dostoyevsky’s exploration of his own Christian faith through his writing was of enormous interest to the Japanese, as there is nothing quite as attractive as

something that has been specifically forbidden. Scorsese’s 2016 film, Silence, tells the blood-soaked story of Portuguese Jesuit priests attempting to secretly enter Japan in the late 17th Century. Many ordinary peasant folk received much comfort from Christian teachings, and it is to be expected that a Christian underworld persisted throughout the closed years. Although enticing, discovery of any Christian artifacts or talk would have resulted in death.

Akira Kurosawa adapted Dostoyevsky’s The Idiot in his 1951 film, Hakuchi, where Prince Myshkin becomes Kinji Kameda, a character who is perfectly placed in the backdrop of war in Japan. Despite some stunning cinematography, and some unforgettable scenes, the film received little acclaim, critics saying that he had tried to cram too much of the original book into the film. They were right. The initial cut of the film was four hours’ long; the studio, against Kurosawa’s wishes, cut it down to just 166 minutes, thus rendering the final release bewildering. It is, perhaps, Kurosawa’s love of Dostoyevsky that ultimately brought about the failure of his film.

|

|

An international conference in 2000 on the theme of ‘The Twenty-First Century through Dostoyevsky’s Eyes- The Prospect for Humanity’ was held over five days in Tokyo, bringing together scholars from twenty-five countries. The importance of dialogue in the works of Dostoyevsky was a key area of report from this conference.

A 2003 Japanese translation of The Brothers Karamazov out-sold any previous publication in Japan, Japanese or foreign. Crime and Punishment has topped the list of most frequently read books in Japan for many years, but I’m afraid that the Harry Potter’s books have more recently stolen the very top spots!

The great literary force that is Haruki Murakami cites Dostoyevsky as his ideal writer, echoing in his own writings Dostoyevsky’s honesty, beauty and strength. In an interview in 2004 with The Paris Review, Murakami said, ‘For me it’s the same thing, Dostoyevsky and Raymond Chandler. Even now, my ideal for writing fiction is to put Dostoyevsky and Chandler together in one book. That’s my goal.’ He went on to explain, ‘You’ve read Raymond Chandler, of course. His books don’t really offer conclusions. He might say, he is the killer, but it doesn’t matter to me who did it. There was a very interesting episode when Howard Hawks made a picture of ‘The Big Sleep.’ Hawks couldn’t understand who killed the chauffeur, so he called Chandler and asked, and Chandler answered, I don’t care! Same for me. Conclusion means nothing at all. I don’t care who the killer is in The Brothers Karamazov.’

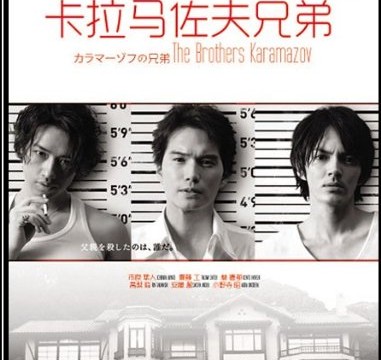

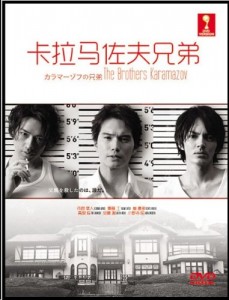

An award-winning 2013 Japanese television mini-series adaptation of The Brothers Karamazov is highly praised by Bristol University’s Russian Studies lecturer, Connor Doak: ‘The series provides a case study in how Dostoevsky has been indigenized for a contemporary Japanese audience. Moreover, it is fascinating to observe how this mini-series is influenced by recent trends in televised crime drama, a genre that, of course, had its origins in nineteenth-century literature, and to which Dostoyevsky’s own novel made an important contribution some 150 years ago.’ The Karamazov family become the Kurosawas. This name offers a respectful nod to the director of The Idiot, but its Japanese meaning, ‘black swamp’, also signifies the book’s haunting theme of blackness.

It seems that the writings of Dostoyevsky will always have a place in the psyche and hearts of the Japanese people. But why? Perhaps it is because his profound and realistic explorations of conflicts between self and others are so closely linked to Japanese heritage, experience and culture.

Want to know about VM Productions’ “Dostoyevsky-Los Angeles Project” and about the films we make? Sign up to get the tickets to the premiere of our movie in post production Dostoyevsky Reimagined-BTS and

grab our FREE e-book (click on the cover below)!

Follow us through our social media on Twitter, Facebook, Google+, Pinterest, Tumblr, Instagram and Goodreads

Follow us through our social media on Twitter, Facebook, Google+, Pinterest, Tumblr, Instagram and Goodreads

We hope to see you back here soon!-

Leave a Reply