In the Russian classic, Notes from the Underground, Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s ‘Underground Man’, the narrating protagonist, recalls a traumatic experience he’d endured involving a young woman called Liza. Underground Man talks of how, after failing to present himself as an intellectually superior human to some popular guys from his secondary school days, in a paralytic state he’d stumbled into a brothel. There he meets novice prostitute Liza; she’s young and has just started the job.

Preferring to engage in conversation than sexual intercourse, Underground Man is acquainted with the injustices of Liza’s circumstance: her careless family suggested she become a whore. Underground Man preaches to Liza alternative means to living her life, speaking also of her beauty. In awe, Liza falls for him, as is indicated by her desertion of the brothel and subsequent arrival at his home the following night.

suggested she become a whore. Underground Man preaches to Liza alternative means to living her life, speaking also of her beauty. In awe, Liza falls for him, as is indicated by her desertion of the brothel and subsequent arrival at his home the following night.

Now, although Underground Man adores Liza, ‘warts n’all’, his theoretical disposition-hindered by his now sober state-leads him to insult her. Unable to accommodate for the social expectations that’d have him embracing the splendid spontaneity of their meeting, Underground Man aggressively makes his dissent known to Liza. It is the predictability and seeming entitlement of society and the social rules it dictates that he now makes known to the illiterate girl.

A far cry from the Russian classic, the despondent ‘down & out’ of today, who’s advocacy of the devil is due to their depressing outlook on life, insolently conceiving ‘yin and yang ain’t gonna cut it for me’ is an analogy that puts Underground Man’s position into perspective. But like is often the case for any individual adamant in denying any of life’s bounties, when the consequences of such unproductive an attitude come about, immediately regret they feel for their refusal. Distraught and bewildered, Liza leaves Underground Man’s house and presumably returns to prostitution.

A far cry from the Russian classic, the despondent ‘down & out’ of today, who’s advocacy of the devil is due to their depressing outlook on life, insolently conceiving ‘yin and yang ain’t gonna cut it for me’ is an analogy that puts Underground Man’s position into perspective. But like is often the case for any individual adamant in denying any of life’s bounties, when the consequences of such unproductive an attitude come about, immediately regret they feel for their refusal. Distraught and bewildered, Liza leaves Underground Man’s house and presumably returns to prostitution.

He rushes after her with the intention of making amends, but the damage is done and she’s gone for good.

He rushes after her with the intention of making amends, but the damage is done and she’s gone for good.

Facing the consequences for our negative actions generally acts as a deterrent, stopping us from committing them again. Contrastingly, post-upsetting of Liza, in addition to feeling regret, Underground Man conceives of an instance where his actions may be positively utilitarian: Liza is now prepared for the men who’d have surely mistreated her in the brothel anyway; he, himself, doesn’t have to readjust his life to fit around Liza and may continue to ‘live underground’ philosophizing and developing most enlightened a mindset. Isn’t it true, however, that we can all find utility in any given circumstance if we look deep enough? I.e., always discover the grass to be greener on the other side … even a death in the family, once overcome, instills in a person a more sympathetic inclination, equipping that person with the skills for consolidating fellows struggling with their own family deaths. But whether the positives outweigh the negatives in any given situation is sometimes unclear, and Underground Man’s conundrum is an example; there is a fine line between pragmatic pondering and wishful wondering.

With respect to Dostoyevsky’s Russian classic, it matters not whether this man is doing one or the other, it’s rather the cursed, insurmountable sums these theoreticians conjure up that we should be concerned with. For knowing where one should mentally draw the line, cease contemplation, and endure the pain of reality would surely be a gem to us all.

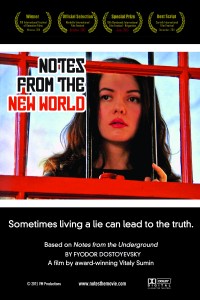

The found footage tale, Dostoyevsky Reimagined: The Making of Notes from the New World (2015) by Vitaly Sumin will give rise to a plethora of philosophical notions for audiences to ponder over, including the ontological:

And all the men and women merely players;

They have their exits and their entrances,

And one man in his time plays many parts,

(William Shakespeare, As You Like It, 1599-00)

-this excerpt will answer those who assert that Dostoyevsky Reimagined: The Making of Notes from the New World is fictional, by pointing out that s/he may be themselves!

The very idea that we’re all actors comes as counter-intuitive to most, but some are more disposed to questioning than others, and discovering ones capacity for such can be an important task … for the most uncomfortable souls, especially.

Follow us on Twitter, Facebook, Google+, Pinterest, Tumblr, and Instagram.

Excellent text. Thank you!