Russian classics tend to be steeped in Russian philosophy, thus revealing the mindsets of Russian culture at the time in the same way an English novel might reveal the social structures and customs of the time in which it was set. What spurs on this difference in style and content is difficult to determine, but the practical offshoot is the Russian classics are some of the most, dense, revealing, and philosophical novels of all time. Russian classics also gave us the first antiheroes; those delightfully normal protagonists are almost completely lacking in heroic attributes but so rich in character and potential philosophical exploration.

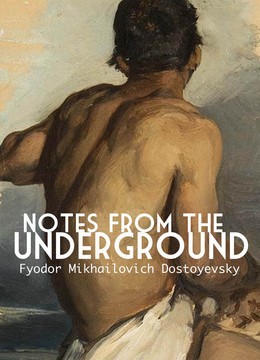

While there are many examples of deeply philosophical writing among the Russian classics, and just about as many antiheroes, I particularly like the mix in Notes from the Underground by Fyodor Dostoevsky. My affinity is partially because the writer of the ‘notes’ directly deals with the popular philosophical ideas of the day, and partially because I feel this is in many ways the birthplace of the modern antihero.  I truly enjoy the slightly deranged philosophical views of the Underground Man on subjects like the ideal of beauty, and his frankly insane overreaction to utilitarian philosophy, but it is his role as a sort of prototype antihero I think really makes the novel what it is.

I truly enjoy the slightly deranged philosophical views of the Underground Man on subjects like the ideal of beauty, and his frankly insane overreaction to utilitarian philosophy, but it is his role as a sort of prototype antihero I think really makes the novel what it is.

The Underground Man is not likable. In fact if you happened to meet him in the street, you would probably dislike him intensely, but I think he makes a great antihero protagonist for the same reason modern antiheroes draw us into stories so much more effectively than heroes do; the truth is we can identify with antiheroes better. As much of a cynical jerk as the Underground Man is, we can all still identify with him because we’ve all had thoughts as dark and unreasonable as his, we’ve all overreacted to ideas we just don’t much like, and we’ve all been jerks to other people for no real reason.

The beauty of the Underground Man, the antihero, and many Russian classics in general, is they validate our imperfections, and allow us an imperfect protagonist with which to identify and in whom to confront our own worst traits. The Underground Man also gives us a rather vivid image of what we can become if we don’t keep our own cynicism in check. The Underground Man sometimes takes ridiculous positions just to protest the norms of a society from which he feels alienated, reducing him from a thoughtful dissenter to a man who won’t go to the dentist when he has a toothache because that would mean he was tacitly supporting the social construct in which dentists happen to be a part.

While this serves, philosophically, to highlight the foolishness of protesting everything about a society because we are disillusioned with certain aspects of it. It also works as a warning to us on a personal level, while we can all identify with the Underground Man to some extent, we are being warned against allowing ourselves to be consumed by our worst traits lest we become as bitter and cynical as the Underground Man in Dostoevsky’s novel.

While this serves, philosophically, to highlight the foolishness of protesting everything about a society because we are disillusioned with certain aspects of it. It also works as a warning to us on a personal level, while we can all identify with the Underground Man to some extent, we are being warned against allowing ourselves to be consumed by our worst traits lest we become as bitter and cynical as the Underground Man in Dostoevsky’s novel.

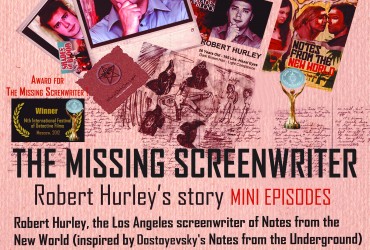

The wonderful thing about Notes from the Underground and other Russian Classics is they are still relevant to us now, we can still get the same catharsis and visceral philosophical warnings today from reading Notes from the Underground, or watching a movie adaptation like Notes from the New World that the original audience could. So let’s hear it for Dostoevsky, Russian classics, and all the wonderful antiheroes who make life easier to handle while reminding us not to let our apathy, cynicism, and bitterness consume our lives; reminding us we must fight not to become as sick as the Underground Man.

Leave a Reply