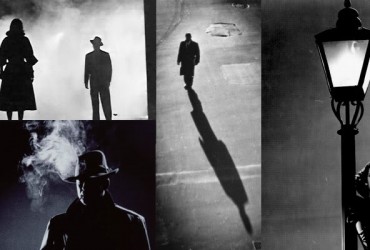

It’s very sobering and equally humbling to see how often ahead of the curve noir films were at their artistic height in the 1940s, despite having been produced in days of great social upheaval and turmoil. Or perhaps because of it. Deservedly better known for his magnum opus The Third Man, Carol Reed had shown the immense potential of film noir a few years prior, drawing from a hot topic with great verve and poignancy, and yet enough poise not to be too explicit.

In his BAFTA Best British Film Award-winning Odd Man Out, Reed explores the conflict in Northern Ireland indirectly, without ever mentioning the IRA (although its protagonist leads and fights for the sake of “The Organisation”), filtering it through the moody lenses of cinematographer Robert Krasker and the quasi-religious pathos and veneer of moral uncertainty that befit a film noir of this stature. The British director adapted a 1945 novel by thriller mainstay F.L. Green, which at the time made the film sneakingly topical. But between striking visual splendour straight out of German expressionism and a tragic finale that reminds of the French realism of Duvivier’s Pèpè le Moko, the emphasis is more on the pervading humanism (or lack thereof) which has defined this genre for decades.

James Mason’s star couldn’t be brighter in the late 1940s, after the success of The Seventh Veil. But while his career-making role as crippled musician Nicholas in Compton Bennett’s 1945 hit saw him portray a man ravaged by jealousy and misogyny, his Johnny McQueen here is a much nobler anti-hero. After expressing doubts about the use of violence for their cause’s sake to his peers, Johnny is fatally wounded after a heist gone spectacularly awry, and we spend the rest of the film following his descent towards the night, as he is surrounded by a world he never seemed to belong to. Wonderfully wounded in spirit first and body afterwards, Mason is immense here, uttering a precious few words but emoting with his entire being, like the most expressive of leads in the great silent films of yesteryear.

Perhaps even more striking, given how they eventually blur together and combine to form a sort of cohesive, all-encompassing character, is the collection of faces that Johnny comes into contact with, essayed by a great selection of Abbey Theater alumni: they’re all seemingly trying to exploit him, or are too afraid of the consequences that helping him would entail. There is the crazy painter trying to use his condition for artistic inspiration, a publican who hides him to avoid trouble, a peddler using him to secure his next meal, and a priest eager to hear his confession.

It seems almost as if nobody surrounding Johnny saw him for what he was, a mortally wounded man on the run from matters truly greater than him, but only for what he symbolized – the ongoing struggle of The Organization. Nobody but Kathleen (Kathleen Ryan), secretly in love with him from the start, and doing her utmost to find him and bring him to safety throughout the film.

After Odd Man Out, producer Alexander Korda introduced director Reed to novelist Graham Greene, who would go on to collaborate with him in two of the director’s most iconic films, The Fallen Idol and The Third Man. But Odd Man Out is a fantastic chance to see the director’s film noir roots at work, in one of the genre’s most eclectic and beautifully tragic examples.

ODD MAN OUT

A film by Carol Reed

Starring James Mason, Robert Newton, Cyril Cusack, Kathleen Ryan, F. J. McCormick

Screenplay by R. C. Sherriff (based upon F. L. Green’s Odd Man Out)

Produced by Two Cities Films

Want to know more about what we do? Sign up to learn more about our process, our projects, and upcoming premieres.

Follow this developing story through our social media on Twitter, Facebook, Google+, Pinterest, Tumblr, Instagram, Goodreads.

Follow this developing story through our social media on Twitter, Facebook, Google+, Pinterest, Tumblr, Instagram, Goodreads.

Leave a Reply